In recent years, microbes responsible for localized malodors - bad breath caused by oral bacteria and axillary odor - have been mapped using next generation sequencing approaches. However, Intestinal microbes responsible for systemic malodor (whole-body and extraoral halitosis), remain to be identified.

Our preliminary analysis of culture-, PCR- and 16S-RNA-based data donated by MEBO and PATM community members show that there are no easy answers.

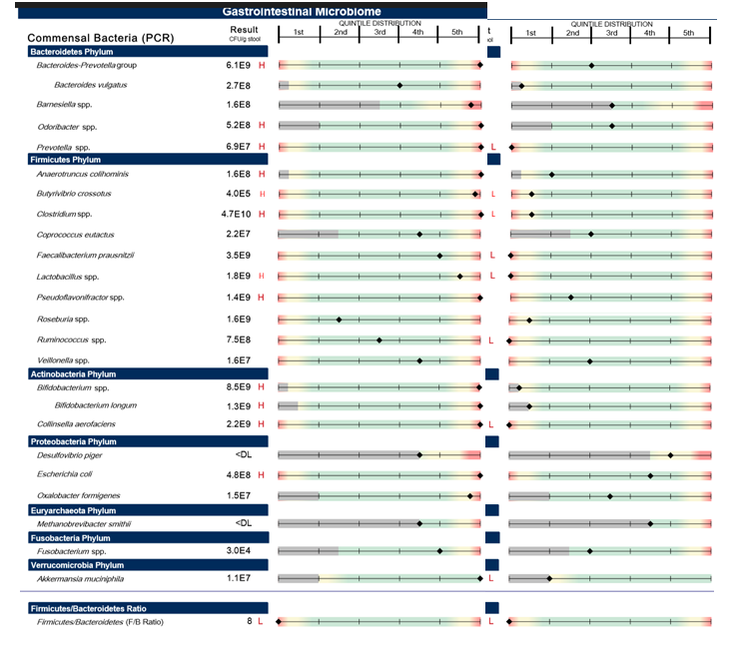

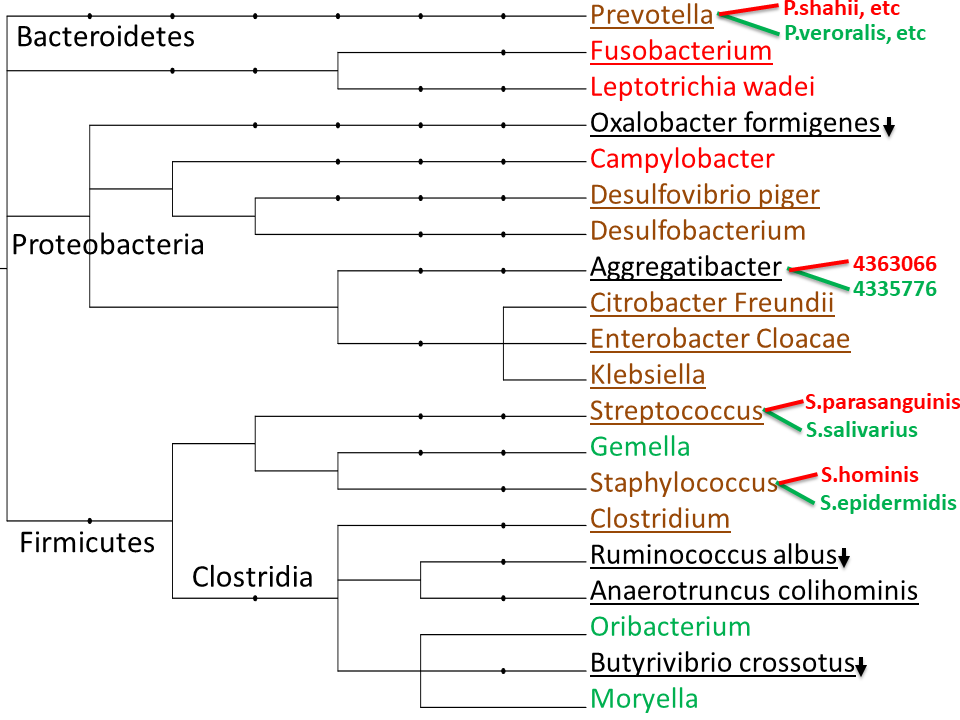

"Lower Firmicutes to get firm and cute," says a news headline. MEBO population is low in Firmicutes and higher in Bacteroidetes. In fact, the very low F/B ratio is just about the only thing in common across the population in the Genova PCR-based microbiome analyses. The figure above shows typical representatives of MEBO "sweet" (on the left) and "non-sweet" (on the right) groups, as defined in our previous posts, video presentations and reports.

Our preliminary findings show that "sweet" group of MEBO community is high in Anaerotruncus colihominis - indole (fecal smell) producing bacteria that utilises sugars glucose and mannose. Everyone seems to be low in Ruminococcus albus - a primary cellulose degrader that produces hydrogen and sweet-smelling acetate. 60% are low in Oxalobacter formigenes. Many participants had higher levels of Proteobacteria - but everyone had their own species - such as E.coli, Citrobacter freundii, Enterobacter Cloacae, Klebsiella or Aggregatibacter. Butyric acid-producing Butyrivibrio crossotus was abnormal in all of our samples: either too high or (mostly) too low. We also observed cases when the gut microbiota was significantly unstable - similar to Crohn's disease (even when patients are in remission).

We owe much of our general good health to the results of bacterial wars when the "good" species are destroying the "bad" invaders. Could it be that systemic malodor arises from bacterial wars that have no real purpose? Our research is only just beginning.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed